Rallying for Women to Rise up the Ranks

Eilín Geraghty and Lars Steffen from the eco Association, on how to tackle the glass ceiling in the tech industry and develop a virtuous circle for women in leadership positions.

© maxsattana | istockphoto.com

Here’s a short story which is likely to ring a few bells. A friend of ours, Tanya*, has been working for the past 11 years as a software development specialist. Looking back, she reflects wistfully on her start-up with a tech company, where she entered as a Grade A graduate with high levels of enthusiasm and ambition. A fellow student from her course started with her at the same time – Tom, a nice young man, but one who had significantly lower grades and what Tanya describes as “a very laid-back attitude”. Who was her boss within a decade? You’ve guessed it: Tom, who has since enjoyed three levels of promotion. So, you might ask: Did Tanya have children during this period of time? Yes, she did – but so did Tom! Tanya’s position in the company meantime stagnated, her passion for her work slumped – and she finally left the company last year.

In this experience, Tanya is certainly not alone. The sad truth is that, as a Forbes article reports, while female entrants to the workforce often start off with a higher level of ambition to rise to top management than their male counterparts, within two years, these aspirations have palled, with men then being twice as likely as women to aspire to the upper ranks.

Here we are witnessing a critical disconnect: Women also want to lead, but a number of factors are holding them back. The upshot is that, according to Hacker Rank’s 2018 Women in Tech Report, women older than 35 are 3.5 times more likely to be in junior positions than men of the same age.

Extent of female leadership in the Internet industry

So how exactly does the Internet industry measure up when it comes to women and leadership? Given that there are far fewer female than male entrants in the sector, and that just one out of every 6 ICT specialists in the EU is a woman, women are already hampered by a significant “ball and chain”. To take a deeper dive into German statistics: here, as the Federal Employment Agency reported in 2019, the proportion of women in ICT management is even scanter than the already very low female share of this workforce, spanning downwards from 14% in IT systems operations to just 9% in the field of software development. The situation in the US is not dissimilar, with Forbes disclosing that female executives comprise just 11% of the total at Fortune 500 companies. The MSCI Index found that, in 2018, women accounted for just 3.2% of CEOs in ICT companies.

What’s creating this glass ceiling?

Here we are confronted with a vicious circle. The absence of female manager role models diminishes women’s confidence in aiming for management themselves – and also reinforces workplace biases concerning women in leadership. Ultimately, disillusionment in terms of promotion prospects is one of the reasons that women often do not stay in the field, even in the medium-term. For example, in Germany, as the 2019 GEWINN project discovered, just 20 percent of ICT women are still in the field by the age of 30. In the US, research from the Center for Talent Innovation shows that women in STEM careers are 45 percent more likely than men to drop out in their first year.

When it comes to women on boards in the ICT sector, we encounter an even more dismal biography. Here, the MSCI Index found that in 2018, there were no female board members on a quarter (25.4%) of all ICT boards – giving the Internet industry the lowest representation of women on boards across all industries.

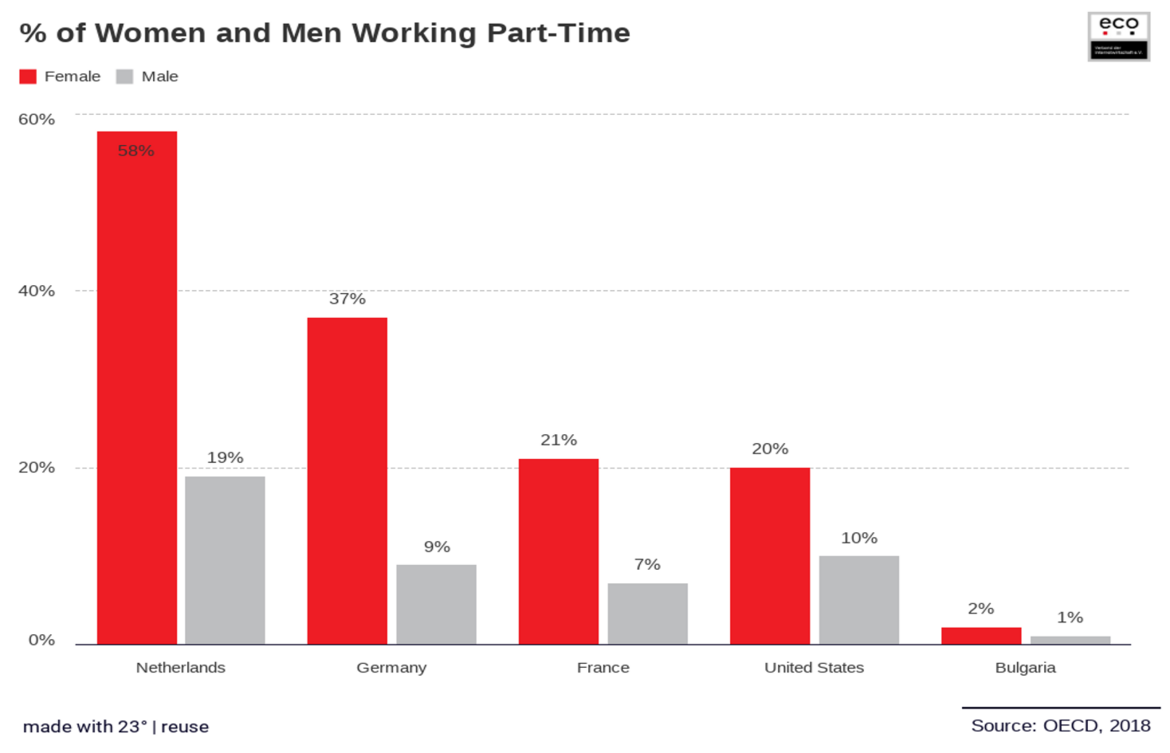

There is also some correlation between the lower levels of women in leadership and the percentage of women working part time. Let’s take a brief look at countries with a lower than average proportion of women in tech, such as the Netherlands and Germany. As the graph below depicts, there are far more women than men working part-time in these countries. This doesn’t mean that opting for part-time work is a misstep in its own right – in fact, as the OECD reports, working fewer hours generally contributes to greater, rather than lower, levels of productivity.

Indeed, there are number of reasons why reducing full-time hours is not only a bold idea, but also a sound one. As the International Labour Organisation contend in their “Future of Work Inception Report”, shorter working hours are positively associated with higher labor productivity per hour due to reduced fatigue, increased worker motivation, decreased absenteeism, lower risks of mistakes and accidents at work, and reduced employee turnover. So the issue here is more about the urgent need for greater gender parity when it comes to both women and men working part time – and for the need to overturn the assumption that, in order to be a manager, you need to have a full-time contract.

Here it’s worth citing Sabrina Waltz of Agency Business 1&1 IONOS SE, who is quoted in the eco Association study “Women in Tech Across the Globe: A Good Practice Guide for Companies” as saying: “My most pressing wish would especially be to have the possibility for women who work part-time to have management careers. This also includes a job-sharing or top-sharing model in which a (top) job is divided in such a way that two people can carry it out. This can be done 50/50 or in any other ratio. This type of co-leadership can also be a win-win situation if experienced managers who are going into part-time retirement share positions with a young manager or a returning parent and thus establish a new management culture.”

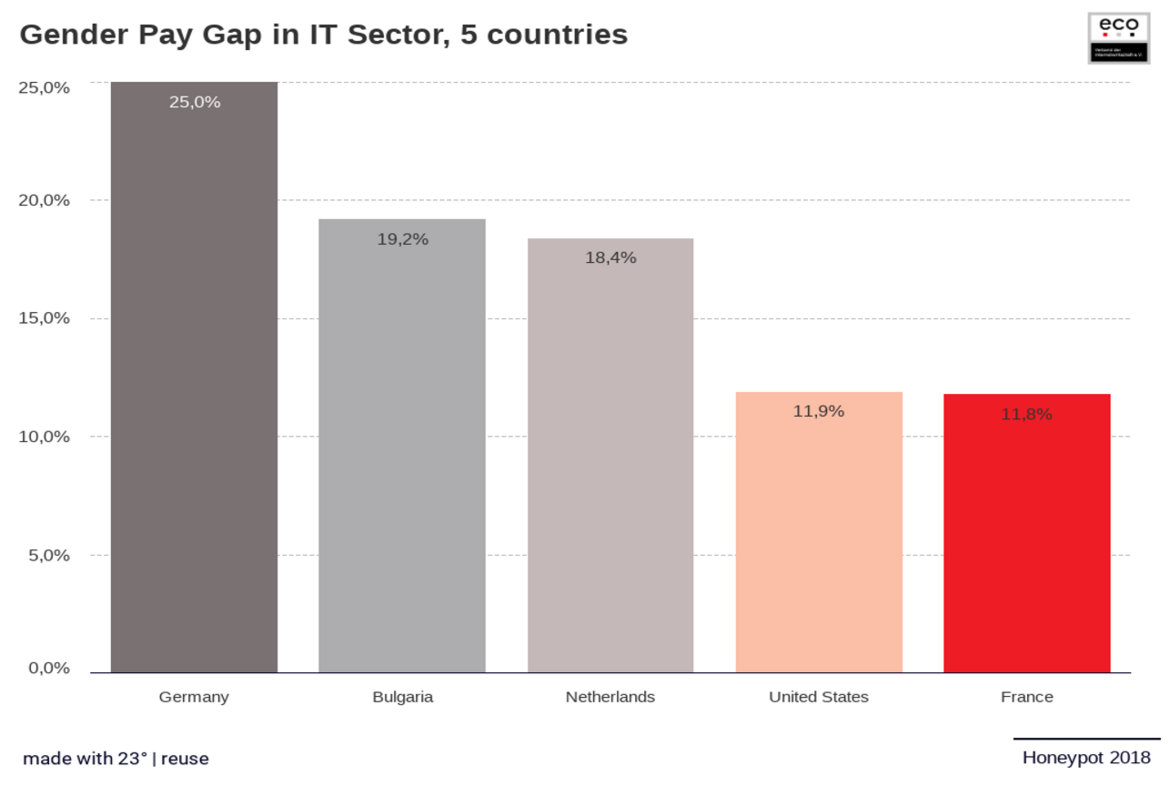

Gender Pay Gap in the Tech Sector

All of the factors already alluded to – fewer senior positions, higher dropout rates, greater numbers of women in part-time work – are contributing to a gender pay gap in the tech sector. This is a gap that exists in the US and across all EU countries (see a sample of countries in the graph below), with one of the highest pay gaps experienced in Germany. While we’ve already pinpointed several reasons for this pay gap, research also shows that women are 4 times less likely than men to negotiate for higher salaries, with this attributable largely to issues of confidence – and, indeed, to how confidence in women can actually be penalized. 61% of women participating in the 2015 KPMG Women’s Leadership Study said they do not feel confident in asking for a raise, while 65% are not comfortable asking for a promotion. All in all, cultural socialization – leading to unconscious biases inbred in both men and women – is at the heart of the incongruity when it comes to women in tech leadership.

As our previous article “Women in Tech – How to Get Started” explains, having more women working in teams and management is in every tech company’s interest. But how can a company set about addressing what is essentially not just an individual challenge, but also a broad societal one?

Luckily, there are strong research findings which show how companies can make a significant difference; initially, for themselves, but also – slowly, but surely – for the industry as a whole.

Number One Action: Sponsorship

Ultimately, the degree to which companies talk about diversity and gender equality matters little compared with how they act. But clearly, this should not involve acting on a whim. A key to success for tech companies is a carefully-developed gender equality plan. And within such a plan, one of the key policies should be that of: Women and Leadership. The Number One lever for change within this policy should be to assign sponsors to women in tech – a recommendation recently elaborated upon in a webinar jointly hosted by eco, the i2Coalition, and the Internet Society by Reg Levy, Head of Compliance at Tucows and Co-Chair of the Diversity and Inclusion Initiative at the i2Coalition.

During the webinar, Reg affirmed that, while women and other people of diverse backgrounds enter the tech industry in reasonably high numbers, they tend not to rise – and that while the proposed solution for some time has been referred to as mentorship, it has become clear that mentorship does not go far enough.

Based on Reg’s experience, “The answer is sponsorship.” She went on to explain that: “Sponsorship is a more active form of mentorship that involves not just advising your mentee, but advocating for them in places that they do not have access to – actively sharing your network connections so that they can forge their own networks and championing their visibility.” Reg urged that sponsors themselves be personally vested in their protegé’s professional development. “A mentor will advise, whereas a sponsor will advocate. You can help your mentee build a career vision, but as a sponsor, you help drive your protegé’s career vision.”

In the eco Association study “Women in Tech Across the Globe: A Good Practice Guide for Companies”, sponsorship is also highlighted as a priority action to be adopted by companies. The study also singles out a range of other recommended actions which are summarized below.

Range of Internal Company Actions for Women & Leadership

1. Encourage a mentality of inclusivity through unconscious bias training. For a further insight into such training, watch a McKinsey video, while free online materials are in the meantime available in several languages from Microsoft. 2. Be transparent concerning salaries and promote the possibility for negotiating pay-rises as a norm within performance reviews. 3. Make sure managers have the required tools and training to fully support their team members – and reward them when they do. |

4. Assign sponsors to women employees, and prioritize this action as a Number One lever for change. For even more tips on assignation of sponsors – and to gain a further understanding of the distinction between sponsorship and mentoring – read a one-pager on the topic from Stanford University. 5. Enlist male allies — VCs, board members, co-founders, etc. — to intentionally seek out women to fill leadership seats. Engage and empower senior male executives to sponsor up-and-coming women. NOTE: Avoid approaches that focus on “helping” or “fixing” individual women; instead, male allies should focus on fixing the environment. |

6. Support aspiring leaders to tap into Women in Leadership mentorship and networking programs, while also supporting women leaders in your company to participate in Women in Leadership mentorship. (Looking for inspiration here? Have a look at a recent article on mentorship: “Nigerian Irish Teen Girls Win Prize For Dementia App”). 7. Champion female managers as role models. 86% of women report that, when they see more women in leadership, they are encouraged they can get there themselves (KPMG, 2015). 8. If your company has only a small number of employees, consider linking to networks, such as: “Femtec.Alumnae e. V.”, The Global Digital Women Network, or The Zonta Clubs. 9. If your company has insufficient women in leadership to showcase, link to platforms such as Inspiring Fifty, or tap into dotmagazine’s Women in Tech interview series. 10. Maintain contact and support with managers during parental leave. For an example of how to approach this, learn about Deutsche Telekom’s Stay in ContacT Network, set up with a view to maintaining a gender-representative quota on leadership positions. 11. Introduce leadership development and performance reward programs with a focus on constructive feedback. Combine “soft” and “hard” rewards. 12. Stress importance of attendance at industry events and use of social media platforms to boost profiles. 13. Enlist women for panels and speaking positions at events. Reach out to networks such as the eco Association’s German “Ladies in Tech” network, the i2Coalition’s Diversity and Inclusion Initiative, or the Internet Society, who can provide panel recommendations. 14. Establish Corporate Professional Development (CPD) programs, to include regular in-house skill upgrading in soft skills, such as leadership training, assertive management, self-organization, and communication. 15. Appoint women to boards and as chairs of working groups. |

Alliances as Key to Women in Leadership

Finally: The actions recommended above are those which companies themselves should consider engaging in internally. But due to the wider societal nature of the gap in women in leadership, companies seeking to positively influence the wider industry should also contemplate engaging in external collaborations. As Agustina Callegari from the Internet Society (ISOC) recognizes: “We all know that there is no simple solution to the digital gender gap and that no single player would be able to narrow this growing gap alone.”

At the recent co-hosted webinar, Agustina shared a case study about Equals, a global partnership that creates a platform representing organizations across multiple sectors, with one of its aims being to develop the leadership potential of girls and women to work in ICT. As one part of this initiative, the Leadership Coalition has developed a course on business and leadership for women in the tech sector, with enormously positive benefits for hundreds of women who have so far completed it. As Agustina explains in her interview “Making the Dream of Gender Parity Reality in the Tech World”: “This impact was thanks to the work of six partners. This illustrates how we can all work jointly on large and small projects to make a positive change.”

Let’s return to the story of our friend, Tanya. Just over a year ago, she moved to a firm where her vivacity and aspirations from the past were instantly and thoroughly re-ignited. One of the most important factors for her is the company’s New Work culture, which includes a great sense of inclusion, flexible working, and face-to-face constructive feedback sessions. But what Tanya also finds very significant is having an assigned sponsor, who for example has already got her to speak on two panels and encouraged her after her first year to negotiate for a promotion. As Tanya reports: “Finally: onwards and upwards”.

* Names have been changed to protect identities.

Download the eco Association study “Women in Tech Across the Globe: A Good Practice Guide for Companies”

Eilín Geraghty is Project Manager in the eco International team at eco - Association of the Internet Industry, and author of the eco Association study “Women in Tech Across the Globe: A Good Practice Guide for Companies”.

Lars Steffen is Director International at eco – Association of the Internet Industry (international.eco.de), the largest Internet industry association in Europe. At eco, he coordinates all international activities of the association and takes care of the members from the domain name industry. He further represents the industry at the Internet Service Providers and Connectivity Providers Constituency (ispcp.info) at the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (icann.org).